Section 1 TBLT Process

I.Contents of TBLT

The misunderstandings about CLT and TBLT and practical concerns expressed by teachers are mainly related to “the introduction of communicative activities (or “tasks”) in which learners are expected to negotiate meaning without the direct control or intervention of the teacher” (Littlewood, 2007: 244) . The concerns and misunderstanding are summarized below (ref. Littlewood, 2007: 244-245; Ellis, 2009: 225-226).

(1) Definition of “task”. The definition of a “task” is not sufficiently clear to distinguish it from other kinds of instructional activities.

(2) Loss of control. CLT and TBLT not only create problems for teachers but also problems of classroom management. Firstly, the activities associated with CLT and TBLT are more suitable for smaller classes and present difficulties of practical implementation in large classes of often unmotivated young learners. Secondly, the role of the teacher in TBLT is limited to that of a “manager” or “facilitator” of communicative activities. The familiar “PPP” sequence (presentation, practice, production) represents not only a way of delivering the language specified in the syllabus but also a way of controlling the interaction in class. This control no longer operates when students are engaged in independent, task-related work. Therefore, there are the discipline challenges in the tension between the need to get the students talking and the need to maintain class discipline (Carless, 2004) . Thirdly, and very importantly, teachers themselves lack the confidence to conduct communication activities in English because they feel that their own proficiency is not sufficient to engage in communication or deal with students' unforeseen needs.

(3) Coverage of language knowledge required by the National Curriculum Standards, including grammar, vocabulary and pronunciation. Firstly, it is not possible to predict what kinds of language use will result from the performance of a task, and thus it is not possible to ensure adequate coverage of the target language in a task-based course. Secondly, because there is no underlying grammar syllabus, TBLT cannot ensure adequate coverage of grammar.

(4) Avoidance of English and minimal demands on language competence. This reflects a perception that tasks and activities often fail to stimulate rich use of the target language. The students may not be using English as the medium of communication in their groups. Instead, many of the tasks result in non-linguistic activity, such as drawing, rather than use of the L2, or there is little L2 production and a wide use of the students' mother tongue (Carless, 2004) . In communication tasks, students may focus on completing the task to the extent that they sometimes produce only the modest linguistic output necessary to complete it. Students are also more inclined to use simple strategies which make fewer language demands (such as guessing) .

(5) External constraints. One of the external constraints is the examination-oriented education system. Many researchers and teachers think that CLT and TBLT are incompatible with public assessment demands because they do not prepare students sufficiently well for the more traditional, grammar-oriented examinations which will determine their educational future. Chinese teachers are often caught between government recommendations on the one hand and demands of students and parents for a more examination-oriented classroom instruction on the other. Teachers', students', parents', and local administrators' concerns about public examinations are among the main factors constraining the implementation of a task-based approach. Another external constraint is that many teachers and researchers believe that TBLT is only suited to “acquisition-rich” contexts but not suited to “acquisition-poor” contexts like China. Still another constraint, independent of the practical concerns mentioned so far, is identified by the many teachers and researchers who have questioned whether the communicative approach is appropriate in countries with “cultures of learning” such as China. The traditional Chinese culture of learning is one in which “education is conceived more as a process of knowledge accumulation than as a process of using knowledge for immediate purposes, and the preferred model of teaching is a mimetic or epistemic one that emphasizes knowledge transmission” (Hu, 2005: 653) . The classroom roles and learning strategies which this culture engenders conflict with a learner-centred methodology such as CLT and TBLT but are highly supportive of a teacher-centred methodology.

Because of the concerns and misunderstandings mentioned above, CLT and TBLT are held back from widespread use and implementation in the Chinese classroom. Underlying these practical concerns, however, there is often a deeper uncertainty about what the approaches actually mean in terms of methodology. There are three conceptual misunderstandings about TBLT. First, TBLT teaches speaking and fluency but ignores grammar and accuracy; secondly, all activities are tasks; thirdly, there is no clear distinction between a task and an exercise.

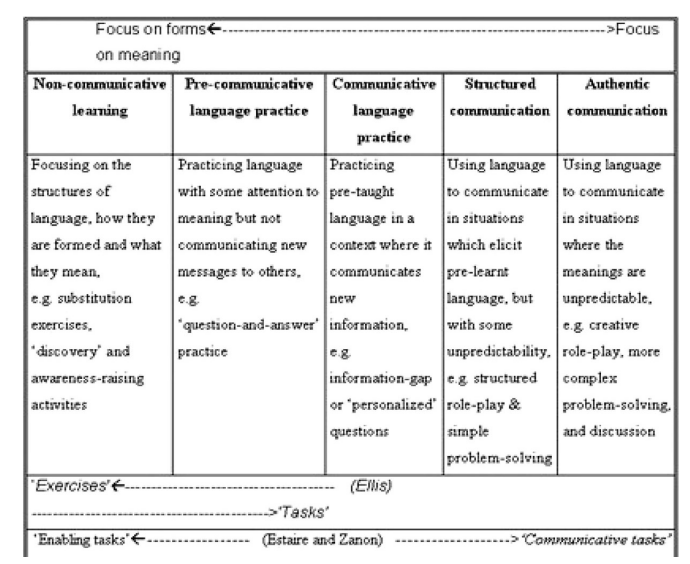

To help teachers understand the concepts and the transition from an exercise to a task, Littlewood (2004) draws the following figure (Figure 7-1) :

Figure 7-1 The Continuum from Focus on Form to Focus on Meaning (Littlewood, 2004: 322)

As is shown in Figure 7-1, the five columns move from Focus on forms (FonFS) gradually toward Focus on meaning and from Exercises (Enabling tasks) to Tasks (Communicative tasks) . The first column of Non-communicative learning involves the strongest Focus on forms . This involves substitution drills and grammar exercises in the absence of any contexts. From there we move to Column 2, Pre-communicative language practice, which still focuses on forms but where there is some attention to meaning. Typical exercises are Question-and-answer practice. Teachers usually ask simple questions like: “What is this? ” or “Whose pen is this? ” or point to some kids in a picture and ask: “What are they doing? ” At this stage, students use fixed sentence structures and the responses are predictable.

The middle column, Communicative language practice, consists of a context and activities with some new information exchange, for example, information-gap and personal information questions. When it comes to Structured communication, learners start using their previous knowledge and newly learned knowledge to communicate, with some unpredictability, to complete tasks such as structured role-play and simple problem-solving tasks. The last column, Authentic communication, focuses on meaning (FonM) and encourages students to use language creatively, solve more complex problems and conduct discussions.

This framework presents clearly the transition from FonFS to FonM. It not only makes connections between non-communicative exercises and communicative tasks, but also links traditional approaches with communicative approaches. This approach accommodates both teachers' cherished teaching concepts and innovative ideas to make teaching more comprehensive, flexible and meaningful.

There are many ways to promote student learning in CLT and TBLT. Negotiation of meaning and focus on form (FonF) are used to help students learn grammatical structures and vocabulary. This negotiation of meaning is a process that speakers go through to reach a clear understanding of each other. For example, asking for clarification, rephrasing, and confirming what you think you have understood are all strategies for the negotiation of meaning. Focus on form “... overtly draws students' attention to linguistic elements as they arise incidentally in lessons whose overriding focus is on meaning or communication” (Long, 1991) . Within a communicative approach, “it refers to learners and teachers addressing formal features of language that play a role in the meanings that are negotiated. This is contrasted with a focus on forms, which emphasises formal aspects rather than meaningful activities (Carter and Nunan, 2001) .” The demo class at the beginning of the chapter is a good example of FonF, because the professor used “car” to elicit the new word “ambulance”. When the professor and the other students helped the boy, there was interaction and scaffolding. It is obvious that the professor had not taught the students structures or vocabulary in advance. Instead, he taught the words when they were needed. He later said that he didn't plan to teach the word “ambulance”, he taught it because the boy was not able to express himself. This kind of FonF is called incidental FonF, and is ideal in that it aims to meet students' needs.

II.TBLT Classes

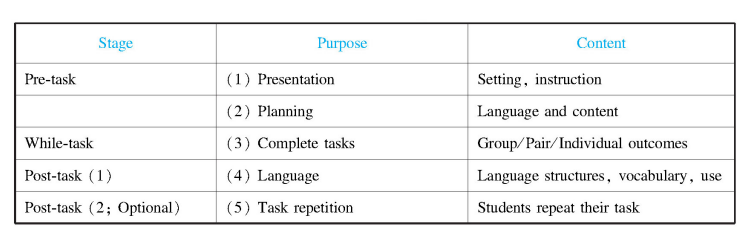

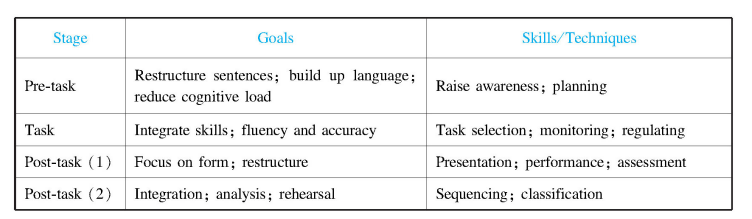

There are usually three stages in a TBLT class,pre-task,while-task,and post-task(Table 7-1.Willis, 1996;Skehan,1996;Ellis,2003). Willis(1996)has proposed a framework for a TBLT class: at the pre-task stage,the teacher introduces the theme of the unit and learners prepare for the tasks. The preparation helps the learners recall words and phrases that are needed for the unit. They can also learn key words and phrases that are essential for completing the task. In the while-task stage,learners work either in pairs or groups,or sometimes individually on a task which might be a reading task or listening task or problem-solving. After that,they report or present orally to the whole class what they have done and what the outcomes are. At the post-task stage,the focus is on form,which could be some structure or vocabulary. The teacher practises with the students and gives feedback on their performance.

Table 7-1 TBLT process

Each stage has different goals and teaching skills/techniques (Table 7-2) .

Table 7-2 Stage goals and techniques

Please reflect:

Are there any differences between Pre-task, While-task and Post-task, and the learning at each stage (Pre-learning, While-learning and Post-learning) ?

Nunan uses the following six steps to design lessons and units of work based on the task-based language teaching framework.

Step 1: Schema building. Develop schema-building exercises that introduce the topic, set the context for the task, and introduce key vocabulary and expressions. When we hear a word or a phrase, we infer the meaning according to our life experience and existing knowledge. At this stage, teachers usually provide students with background knowledge and vocabulary related to the topic.

Step 2: Controlled practice.Provide students with controlled practice in using the target language vocabulary, structures, and functions. For example, we can present a dialogue for students to listen to or imitate. Students can also do other simulated tasks based on the samples provided in Step 1.This stage is not simple repetition or mechanical exercise but a step toward paying attention to meaning according to the context or situation.

Step 3: Authentic listening practice.Involve learners in intensive listening practice with native speakers performing the target task (s) . The listening materials are not restricted to previous sample dialogues or short passages, but are materials related to the topic with some changes in the content. The purpose of this is to expose the learners to more authentic materials and broaden the input. The listening practice doesn't have to be very difficult; it could be a direct link to broadcasts such as BBC or VOA.

Step 4: Focus on linguistic elements.Get students to focus on pronunciation and grammar features. This step seems to be similar to the usual first step in the traditional approach in which grammar and vocabulary are introduced. However, it is not exactly the same because the students have already done the first three steps and are provided with a context and are therefore ready to learn the structure and new words that they have heard or read in the first three steps. Thus, the language form is learned and analysed in context instead of in isolation.

Step 5: Provide freer practice.Engage students in freer practice, where they move towards creative language use. Previous tasks or activities are mostly controlled practice within the frame of the samples provided. At this step, students work on less controlled tasks such as information-gaps or other pair work tasks. They can also have simulated real-life conversations based on the samples. The purpose of this step is communication that requires students to use the language they have learned. At this stage, they are expected to maximize what they have learned and acquired.

Step 6: Introduce the pedagogical task.Complete the pedagogical task. This step is the display. Students show and perform what they have done in a lesson.

In sum, in TBLT, we usually use the theme of a module or the topic of a unit as the centre of learning and we design or select tasks around that theme. Teachers then plan their teaching by using the tasks in order to promote language learning and use within a communicative context. Thus, we ask the following three questions before we decide on what tasks to use: (1) How can we relate language form to the theme? (2) How do we integrate language knowledge and skills with the theme? (3) How does output relate to the theme? The procedure could be that the teacher explores the theme/topic and introduces some related words and phrases. Then s/he assigns tasks for the students to work on. Students complete tasks individually or in pairs or groups while the teacher plays the role of a facilitator. Once the tasks are complete, the students report or present their outcomes orally to the whole class, or in writing to the teacher or other groups. Towards the end of the lesson, the teacher summarises what the class has done and draws attention to certain language features and usage.

(I) Pre-task stage

The pre-task stage is a very important stage in TBLT. In this stage, a learning environment is being built through different types of explicit or implicit input. The purposes are: (1) to activate students' existing knowledge and help restructure their language system and ways of thinking; (2) to prepare their necessary linguistic knowledge and cultural knowledge for accomplishing the required tasks. This stage also helps students learn actively and reduce the cognitive load for the next step of the target task.

The pre-task stage consists of task presentation and planning. It is a key stage that determines the success or failure of the TBLT class. Some teachers may think that students of lower proficiency level are incapable of accomplishing tasks. However, based on our observation, in most cases, it is because there is insufficient planning to support the task accomplishment. Skehan (1996) points out that there are two focuses of tasks at the pre-task stage: one is the overall cognitive demand of the task and the other is the linguistic factors. In other words, if the pre-task stage reduces the cognitive load, learners can pay more attention to the language required. Therefore, at this stage, there are many “non-task preparation activities” (Ellis, 2003: 246) such as brainstorming and mind maps (Willis, 1996) for teachers to choose from. These activities aim to reduce the cognitive or linguistic demands placed on the learner. “Activating learners' content schemata or providing them with background information serves as a means of defining the topic area of a task.” (Ellis, 2003: 246) .

1.Using Mind-maps

Mind maps are one type of schemata. In Kantian philosophy, a schema (plural: schemata) is the procedural rule by which a category or pure, non-empirical concept is associated with a mental image of an object. Mind maps, invented by British psychologist, Tony Buzan in the 1960s, have been used in other forms for centuries in learning, brainstorming, memory, visual thinking, and problem solving by educators, engineers, psychologists, and others. Buzan claims that the mind map is a vastly superior note-taking method that uses the full range of left and right human cortical skills, balances the brain, taps into the apocryphal 99% of one's untapped mental potential, as well as intuition (which he calls “superlogic”) .

Mind maps have many applications in educational situations, including note-taking, brainstorming, summarizing, revising, and general clarification of thoughts. Mind maps can be drawn by hand, either as “rough notes” during a lecture or meeting, or can be more sophisticated in quality. Mind maps can be used for:

●Problem solving

●Outline/Framework design

●Group discussion/planning

●Marriage of words and visuals

●Individual expression of creativity

●Condensing material into a concise and memorable format

●Team building and enhancing work morale

Using mind maps, one can listen to a lecture and take down notes of the most important points, or note keywords for later use and reconstruct them to retrieve information. In teamwork, team members can combine their mind maps, decide on the important points, add new ideas (creativity) and construct a common new mind map. As for individual creativity, one can write down all the ideas including old and new ones, and then combine the ideas and restructure the mind map. During this process, creativity can be stimulated with clear goals in mind. Mind maps can help us prioritize before taking action and solving problems. When we need to express our ideas, mind maps can help us clarify and structure our thoughts so we can present ourselves better. Mind maps can help us make individual plans, action plans, research plans, questionnaires, writing plans and meeting plans.

2.Activating background knowledge

The cognitive approach to language learning by Skehan (1996) refers to the topic, background knowledge and knowledge about the task to be accomplished. In general, the topics in most elementary and middle school textbooks are related to students' daily life, for example, school life, family life, holidays and festivals. Students, especially those in cities and towns, are familiar with such topics, but there are cultural differences among the regions. These topics may not be so familiar to those from rural areas or developing regions and may cause unnecessary cognitive demand. Aspects of culture popular in the West and urban areas in China, such as fast food, holidays, sports, transportations, eating habits, housing, etc., may be difficult for students in the countryside to understand. According to research, there are instances of teachers not being sure of some of the topics. When the topics are related to history, culture, geography, literature, the environment and technology, teachers have to do lots of research in order to make the materials or topics more accessible for their students. To those urban students who are familiar with the topics, the teacher's task is then to activate their prior knowledge so they are able to retrieve and access that knowledge and use it in completing the task.

In classrooms, teachers can use mind maps as warm-up activities to teach vocabulary. For example, the teacher can present a poster of daily routines (Figure 7-2; see also Gong & Luo, 2006) , which include getting up, washing, having breakfast, going to school, having a lesson, doing recreational activities, and having supper. The teacher can use the poster to ask questions and practise language structures or vocabulary. The teacher can use words with the pictures to lead the students to practise the words and phrases. If it is a lesson about outdoor activities, the teacher can start the lesson by asking what students know about outdoor activities and what activities they usually do. The students may name many kinds of activities (in either Chinese or English) such as swimming, skating, mountain climbing, skiing or running. The teacher may add more activities by showing some slides and elicit what the activities are. This way, students not only recall what they know already but also learn new words and material in a very natural way.

3.Introducing new materials

Before students learn new target language, they are presented with new material. Task-based language teaching places much emphasis on preparing students to learn new target language and encourages them to use their existing knowledge and experience and relate these to what they are going to learn. This process is a construction of knowledge and making connections between what is already known and the unknown. For example, in a class about “travelling”, the theme and new words could be presented through the following questions:

●Why do lots of people like to travel? Make a list of reasons.

●Are there any interesting places in our province or region? What are they? Look at a map of China.

Figure 7-2 Activating students' prior knowledge

●Imagine you and your partner want to travel to a place far away from your hometown. You prefer to fly there so that you will be able to stay there longer. Your friend has a different idea. S/he believes that travelling by train or boat is more enjoyable. Please discuss this.

When students don't know how to say what they want to say, the teacher can teach them then and there. The students can be given the questions beforehand and prepare for them by referring to dictionaries or other resources and then come to discuss them in groups in class.

4.Sample tasks

Ellis (2003) has proposed other activities at the pre-task stage such as providing students with a task sample, or work on a similar task and plan. Demonstrating a task is a kind of presentation which students don't participate in through expressing themselves, but through observing how a task is accomplished. In elementary schools, we often notice that teachers invite students to work with them at a task first. For example, when a lesson is about shopping, the teacher would ask a student (usually of high proficiency level) to come to the front and act as a shop assistant or a customer with him/her. This could also be a film clip or a series of slides to show the shopping process. While acting, the teacher deliberately draws students' attention to how the salesperson offers help and how the customer responds. Before such a demonstration, the teacher introduces the setting, the people and their relationships, selected language and language functions to reduce the cognitive demand. When students notice the new words or expressions, the teacher will focus on form and, if necessary, point out the differences in different cultures. This is what we call “consciousness-raising” in either culture or language. Following that, it could be language practice, or as Willis calls them “enabling tasks” of grammar or vocabulary practice. The different types of tasks at the pre-task stage could be integrated. Figure 7-3 presents the characteristics of a demonstration task (Gong & Luo, 2006).

Figure 7-3 Demonstration tasks

5.Imitation and practice

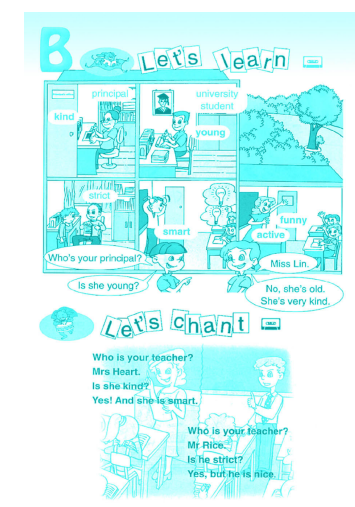

Rome was not built in a day. This applies equally to students' language competence. Having observed the sample tasks, students can start from simple tasks (for example, Figure 7-4.Gong & Luo, 2006) . The teacher has to make sure that the majority of the class are able to complete simple tasks through practice with each other (scaffolding) . Most tasks at this stage are completed in teacher-student and student-student patterns. The focus might be some new expressions or lexical chunks, or even just on sentence structure that the students have learned before. It doesn't matter what the focus is, the most important thing is that we must prepare the students to become ready to accomplish the task in the next stage of the lesson. Teachers must be aware that “imitate and practise” is not simple mechanical copying or repetition; the students still need to think of what they want to say and what their ideas are. During this process, everyone should hear the correct expressions from the teacher or other students, so when they speak, they will pay attention to the form and meaning and consciously correct themselves by using accurate language.

Figure 7-4 A simple task

6.Task planning

One very important thing at the pre-task stage is what Ellis (2003: 247) termed strategic planning . There are quite a number of studies on planning and its effects. From what we have observed in English classes, other than the effects of language proficiency, the main reason for unsuccessful task completion is that teachers do not budget planning time for the students in their lesson plans. In most cases, the teacher presents a task sample and students are given the task and told to work in groups or pairs. However, a number of studies have shown positive effects of strategic planning on fluency and complexity, and with mixed effects on accuracy (e.g., Foster & Skehan, 1999) . In general, planning helps students plan the how, why and what in accomplishing a task. Ellis (2003) has summarized three components of planning: learners are given enough time to plan; learners are given clear instructions on how to plan; and learners are advised to plan individually. This was found to work best for complexity and fluency (Foster & Skehan, 1999) .

Willis (1996) also considers the pre-task stage very important because the clearer the teacher explains the learning goals the more confident the students are in accomplishing the task. The clarity of instructions about a task carries much weight in the success of task completion. Take the following task instruction as an example:

Task instruction: Find seven differences between them and give at least two reasons . A better way would be:

(a) Inform students what your teaching goals are, especially the purpose of your tasks, and what you expect the students to do and in what way.

(b) Give students enough time to plan. Planning time is given in relation to the complexity of a task.

(c) Provide students with necessary resources such as sentence structures, vocabulary, or lexical chunks.

(d) Give students options in completing a task, especially for beginners and weaker students.

(e) Planning (with appropriate instructions) could be teacher-led, group- or pair-based, or individual. Individual planning is the most effective (Foster & Skehan, 1999).

In summary, planning “can lead to greater complexity, either because more complex language is prepared, or because the planning time is used to formulate more ambitious content for messages. Planning, most of the time, will predispose learners to try out ‘cutting-edge’ language, or to be pushed to express more complex ideas” (Skehan, 1998: 74).

In this section, we have discussed the pre-task stage in TBLT. The main functions of this stage are:

(1) To introduce new language in a context;

(2) To increase opportunities to restructure the existing language system. Pre-task activities can enable the students to use what they have learned previously in a different situation and make connections with the new language;

(3) To mobilize existing language. Pre-task activities not only input new language and use but also create opportunities to use their existing language resources;

(4) To recycle language. One condition for language learning is to use language again and again. When we design tasks, we have to consider which language is to be reviewed and which is to be consolidated and which is to be learned;

(5) To reduce cognitive and processing load. Pre-task activities help reduce learner cognitive demand and boost retrieval of prior knowledge;

(6) To urge students to understand the target task. In order to accomplish the task, it is important that students understand the task and the requirements of the task. Therefore, the pre-task stage will affect task completion.

(II) While-task stage

The task implementation stage is a process of language acquisition. At this stage, the teacher pays attention to not only the fluency of language but also the accuracy, and encourages students to reconstruct their language. During this stage, the choice of task is the key and the teacher must select the appropriate task difficulty level, because if the difficulty level is beyond the students' cognitive level, they will not learn anything and lose confidence and interest in learning. However, if the difficulty level is lower than the students' cognitive level, they will also lose interest in learning. Suffice to say, it is not easy to select tasks of appropriate difficulty levels and very often in our teaching we find tasks that are either too difficult or too easy. What teachers can do is to understand the notion of difficulty and think of different ways to reduce or increase the difficulty.

For example, if a task is too difficult, we may use graphs or pictures to make it easier; if a task is too easy, we can modify the task by adding more pieces of information or making it more demanding and require critical thinking such as turning it into a task about opinions or problem-solving.

In completing tasks, there will be all kinds of pressure for the students. To reduce such pressures, the teacher can adjust the task time, task mode, or the number of participants. It is important that the teacher assigns students tasks that they can manage.

The two common ways of completing a task are individual work and group work (which includes pair work) . Group work is most widely used in current classroom teaching. What should be noticed is that, in TBLT, individual work is as important as group work, and not all tasks require group work. Some reading and writing tasks, for example, are more appropriate for individual work.

1.Group work

Group work, including pair work and collaborative work, is one of the characteristics of TBLT. From a socio-constructive perspective, human linguistic competence is developed in social interaction. Jacobs (1998, cited in Ellis, 2003: 267) provides a comprehensive list of potential advantages of group work compared with teacher-centred instruction:

2.Individual task and group task

Although group work and collaboration are important in TBLT, individual work and whole class activities are just as important. Instead of rigidly assigning students group or individual tasks, it is vital that the teacher understands the nature and requirements of the tasks so as to assign tasks to groups or individuals accordingly. From a pragmatic perspective, there is a lot of individual work in authentic communicative settings and individual work is also interactive in some sense. For example, when listening to the radio, one interacts with the narrator; when watching TV, one interacts with the TV program; when reading books or newspapers, one interacts with the heroes or heroines or the news. From a learner's perspective, introverted students may not do well in group work but may perform well in other settings. According to our observation and experience, some students may perform well orally but are less accurate than those who are not very expressive. There are tasks that could be done both individually and in group work. Take the following as an example:

In the text, the author talks about three kinds of problems: environmental, animal and human. For each statement below, label the kind of problem being described. Analyse the sensory language (words that describe how something looks, sounds, feels, smells, or tastes) .Underline words and phrases that help you decide what is happening.

A. Sight B. Sound C. Taste D. Smell E. Touch

In this task, students can read the text individually first, then discuss it in groups, and finally complete the task. But for the task below, group work can be done first and then followed by individual work.

With a group, brainstorm three different solutions to ...'s problem.

Group A: ____________________

Group B: ____________________

Group C: ____________________

When you brainstorm, everyone contributes ideas. Write down all your ideas ...

3.Some issues in implementing TBLT

In designing tasks, teachers need to be clear about the goals of language competence and skills. We have mentioned earlier that the ability to use language consists of different skills. The four skills of listening, speaking, reading and writing, can be separate abilities or components of language competence. Ellis (2003: 276) has proposed eight principles in guiding the implementation of TBLT among which is to “Establish clear goals for each task-based lesson”. The goals of TBLT instruction do not only include language structure and vocabulary but also consist of accuracy, complexity and fluency (Skehan, 1998) . The goals can also be developing learning strategies or integrating prior lessons, not necessarily just the knowledge or skills taught in the unit. In a task-based lesson, there should be a variety of goals to ensure systematic language development. In reading for example, if our goal is to teach reading strategies, we can design reading tasks accordingly (Skehan, 1998) .

Here is a list of sub-skills for reading in some middle school textbooks: (1) Understanding cause and effect; (2) Making connections; (3) Comparing view points; (4) Evaluating ideas; (5) Reading between the lines; (6) Making judgments; (7) Making comparisons; (8) Interpreting meaning; (9) Making inferences; (10) Comparing characters; (11) Reading a map; (12) Interpreting graphs and charts; (13) Making calculations; (14) Examining reasons; (15) Separating facts from opinions; (16) Identifying the main idea; (17) Organizing information; (18) Sequencing; (19) Summarizing; (20) Recalling details; (21) Synthesizing; and (22) Drawing conclusions.

When we ask the students to do a task, we must have clear goals for each task. What do we want our students to learn and to do? In the lesson “Finding Your Way”, students are expected to complete linguistic and communicative tasks related to that theme/topic, such as answering the phone or listening to the phone message to take notes of the directions to a destination, or asking the way and finding the destination on the map. I have observed lessons on many occasions and noticed that there are usually as many as about ten tasks in one lesson: listening, speaking, watching videos/slides, individual work, groups work ... In the end I do not remember what the teacher has taught and what students have learned. What I do remember is the teacher asks students to do a task every two or three minutes. As a result I am not clear about the goals and purposes of the tasks. In fact, the quantity of tasks does not count in a lesson, what counts is the effect of the tasks. If a listening task simply asks students to listen and answer questions, and the teacher does not give any/enough instructions or guidelines by providing the context of the listening task, what the students should listen for or what goals they are to achieve, it is not a good task and there will be little benefit in doing such a task.

4.Teachers' role

With the implementation of TBLT, the role of the teacher has been changed to some extent.

However, it should be noted that some versions of TBLT are in fact entirely teacher-centred. Prabhu (1987) , for instance, distinguished between a pre-task, which was to be performed by the teacher in lock-step fashion with the whole class, and the main task, which was to be performed by students individually. He argued that it was only the teacher who could ensure the “good models” of English needed to promote interlanguage development and that “sustained interaction between learners is likely to provide much less opportunity for system-revision” (p.81) ... (Ellis, 2009: 236)

According to Ellis (2009: 236) , in almost all versions of TBLT, including those that prioritize group work, the teacher not only functions as a manager and facilitator but also needs “to direct learners' attention to form during the performance of the task” and “engage in various types of pre-emptive and reactive focus on form. ... They adopt both implicit and explicit corrective strategies, at times intervening very directly to ‘teach’ about some item of language”.

It is obvious that TBLT challenges teachers who need time to adjust themselves. They could start by intervening less when students work in groups (see Willis, 1996) and being more confident in their students. Willis suggests that, instead of correcting students' pronunciation right away or giving suggestions in advance, teachers should provide help when needed. A major task for the teacher is to ensure that every group knows what they are doing, and that every student gets involved, and communication is occurring.

5.Explicit instruction

Other than the pre-task preparation, samples, background knowledge, and having enough exercise, the success or failure of a task lies in the clarity of the teacher's instruction when s/he assigns the task. In many cases, the teacher may just say one or two sentences and the students start working. As a matter of fact, many students are not even clear on what they are doing. I often hear them ask each other in their groups, “What are we doing? ” Therefore, it is essential that the teacher give clear instructions before the group work.

Clear instructions may cover the following:

(1) Goals and requirements.Tell students explicitly the purposes of the task and the requirements. If necessary, give them samples. If it is to listen to the tape, tell students what the topic is, what kind of information they need to listen for, what they should do when listening and what they are expected to do after this.

(2) Roles in the group.Assign roles and responsibilities to group members; for example, who is the presenter, who is taking notes, etc. This could be decided within the group. Only in this way will students actively participate in the task. Otherwise it is group work only in form.

(3) Ways of completing the task and resources needed.If the teacher wants students to compare different cities in terms of their architecture and city plans, s/he must provide students with maps, a list of what they are to compare, and ways to find the relevant data.

(4) Time control and Attention to individual differences.

While it is important that the teacher sets a time limit for task completion, it is necessary to be flexible sometimes. If 2 or 3 minutes are given for a group task, the students may have to stop before they even start! It is the teacher's responsibility to monitor the task progress and adjust the time limit according to how the students are responding. Requiring the students to finish doing all the tasks prepared for a lesson is not a necessity but the quality of the task output is vital. If the majority of the students are not interested in a certain task, it is important to stop doing the task. Sometimes when there are students of mixed levels in a group, it is the teacher's responsibility to make sure that both advanced and weak students get the opportunities to speak and perform.

(III) Post-task stage

As we have mentioned earlier in this chapter, TBLT focuses on both fluency and accuracy and pursues not only communication but also practice. In fact, in a task-based lesson, we can attend to language forms at any phase of TBLT (Ellis, 2003) , though this is more likely to be the case at the post-task stage. At this stage, students are given opportunities to repeat the tasks and are encouraged to reflect on the process of task accomplishment and focus on form. The post-task stage includes the following activities:

1.Task repetition

When students work in groups at the task stage, they may pay more attention to the results of the tasks and might have ignored the language form and accuracy. When they redo the tasks and report their group's achievement to the whole class, their attention is likely to be directed to language accuracy and complexity. They do not simply repeat the work; instead, they complete the tasks independently and try to improve their accuracy, complexity and fluency. Through task repetition, students reflect on the weaknesses and mistakes they have made, and become clearer on the relationship between language form and function in their internal language system. Thus the purposes of the post-task stage are reflection and language consolidation. Teachers need to design tasks that can raise student awareness of language accuracy.

One way to achieve this is to let each group report their achievement to the whole class. As one student reports, the rest of the class take notes of what he/she says for later comments. It would also be meaningful to record what the student says and let the student or the whole class listen to the recording and see if they can give feedback on grammatical errors. Other tasks for accuracy could include the following:

●In group discussion, one or more students take notes;

●When each group reports to the class, the rest of the students take notes or list their comments, or compare their results with other groups;

●Listen to the recording or watch a movie to do an information-gap task or fill in forms;

●Read a form and turn it into a passage;

●Read a passage and find some expressions about an event. For example, time connectives, first, then, finally, etc.

●Copy from a dictionary one or more sentences that contain a word in the text.

2.Student reflection and feedback

In the process of reflection, if it is necessary for the students to be aware of their problems in grammar, there should be opportunities for them to notice such problems. One way of doing this is to do dictation to raise students' attention to accuracy. Another way is for the teacher to take note of students' mistakes in their performance and analyse and explain the common mistakes afterwards.

At the post-task stage, there could be a large number of awareness-raising tasks, though this could be at any stage of TBLT. At the post-task stage, attention can be focused on practicing one language form. The practice can be traditional mechanical drill patterns such as repetition, substitution drills, filling in blanks, restructuring sentences, dialogues, etc. Such activities are necessary for students' language automatization. Teachers can classify tasks, list them and explain the connections between them. They can also explain one grammar item based on the tasks or student performance and describe in detail the grammar usage by using examples in the tasks.

In sum, post-task activities still need to focus on both form and meaning. Thus, teachers can use different types of tasks such as description, narration and comparison, starting from simple description and narration and moving to more complex comparison and argumentation, or from writing notes, cards, announcements, letters and stories to creative writing. Writing tasks can take different forms and incorporate different techniques such as information change, induction, deduction, summary, and comparison. Students are encouraged to do self, peer, and group editing with models and samples provided.

No matter what methodology we use, it is necessary to attend to form and accuracy, especially for ESL learners. Rome was not built in a day, and it takes time and effort to write accurately and fluently. Therefore, when we design tasks for our students, we must bear in mind that different tasks are for different purposes. It is important that we know what tasks help their fluency, what tasks help their accuracy and what tasks help their complexity. When students can speak fluently, we must pay attention to their accuracy. Accuracy tasks are not necessarily mechanical or copying exercises, they can be integrated into opinion tasks or other tasks that are related to their life and experience. Only in this way, will students find the activities meaningful and become real language users.

【Practical Analysis】

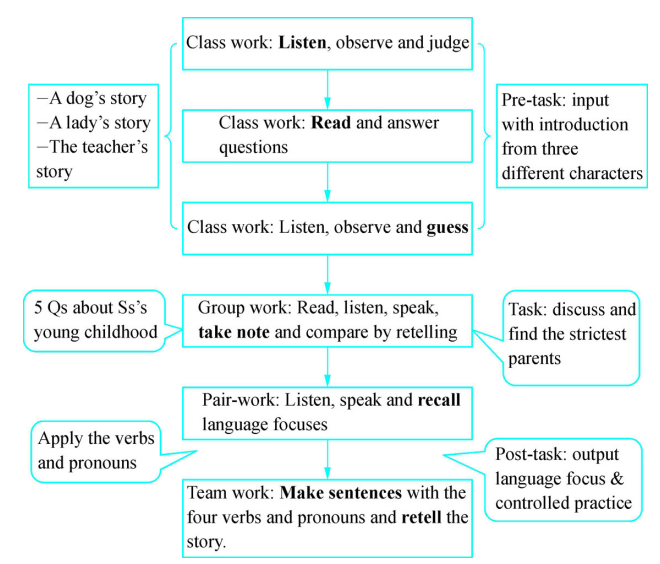

Below is a teaching framework designed by a teacher of 7th graders. Analyse the feasibility of the framework according to what is introduced in this chapter about TBLT.

The Framework of Teaching in Class 1, Grade 7

Topic: Whose parents were the strictest?

Note: The boldfaced words are meant to be the main skills practised. And the colored words are a reminder that helping Ss to go through their notes is vital for the debate.

Next, let’s do some other exercises.