Section 1 Management Strategies

I.Definition and Importance of Classroom Management

1.Definition

Classroom management in language teaching refers to “the ways in which student behavior, movement, interaction, etc., during a class is organized and controlled by the teacher to enable teaching to take place most effectively. Classroom management includes grouping students for different types of classroom activities, use of lesson plans, handling of equipment and teaching aids, etc., and the direction and management of student behavior and activity” (Richards & Platt 2000: 65).

According to Brown (2001), classroom management encompasses different factors, such as the classroom itself, the teacher's voice and body language, midstream lesson changes, teaching under adverse circumstances and creating a positive classroom atmosphere.

2.Importance of classroom management

Planning and preparing for lessons are very important. The implementation of this through the organization and management of a class are also crucial for its success. Seating arrangements, instructions and activities used in class all affect the outcomes of the teaching. The same lesson plan may produce totally different results solely because of different classroom management. Similarly, the way we change a plan in class may also produce different results. “It is shown in research that good classroom management has a positive correlation with students' learning achievement and negative correlation with students' negative emotions” (Lu & Wang 2006: 152) . Therefore, classroom management helps determine whether a class will be successful or not.

II.Classroom Management Strategies

1.Seating arrangement Strategy

We should adhere to four principles when making seating arrangements. Firstly, the arrangements should serve the purpose of the class, i.e. they should meet the needs of different classroom activities, such as student presentations, role-plays, etc. Secondly, it should be convenient for teachers to walk around the classroom. Thirdly, it should be easy for teachers to monitor the whole class, paying attention to every student. Fourthly, it should be easy for the students to see the teacher's presentations as well (ibid., 154) .

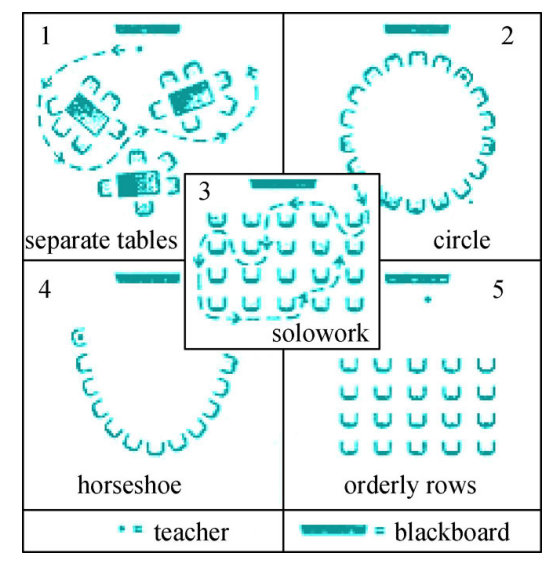

Harmer (2000: 18) suggested the following seating arrangements, as shown in Figure 5-1.

Figure 5-1 Different seating arrangements in class

Orderly rows are suitable for work with the whole class for activities such as clarifying a grammar point, watching a video, using the board, or demonstrating text organization on an overhead transparency. This arrangement has obvious advantages. Firstly, it is easy for us to monitor the whole class. Secondly, we can explain language points and maintain eye contact with our students. Thirdly, it is easy for us to maintain good classroom discipline. Fourthly, our students can see us easily.

Circles and horseshoes are suitable for classes with fewer students. These arrangements are conducive to promoting a more equal relationship between our students and us. Our students can also communicate with each other more easily. Thus, these seating arrangements are good for group performances and class discussions.

Using separate tables makes it easy for us to walk around and check our students' work and help out if they have difficulties. In such classrooms, different groups may work on their own activities in group discussions, preparation of role-plays and problem solving activities.

Solo work, compared with group work, allows our students to work at their own speed managing their own time and studying with more ease.

Brown (2001: 412) suggests, “If your classroom has movable desks and chairs, consider patterns of semi-circles, U-shapes, concentric circles.”

In China, classes are usually large with more than thirty students, so we should plan seating arrangements accordingly. Orderly rows may be used for everyday teaching, but we should try to have even rows and even numbers of seats per row, so that we can organize pair and group work easily. If what we plan to do in class requires furniture to be moved for such things as role-play, debate or other similar activities, we may ask our students to arrange the seats before class. Separate tables for small groups can promote interaction among the groups and may be a refreshing seating arrangement for our students.

2.Instruction Strategy

When we give instructions in class, we should stick to the following principles: “... the principle of clarity, principle of demonstration, principle of checking, principle of appropriate time, principle of advance organizer, principle of complete instruction, principle of clear start and ending” (Lu & Wang 2006: 153). Firstly, our instructions should be clear and brief, so that our students will know what to do without the need to guess. Secondly, we should demonstrate what to do when explaining the activity, especially if it is the first time the students are doing that kind of activity. Thirdly, we should check if our students have understood the instructions. Fourthly, the instructions should be given at an appropriate time or point in the lesson. Do not hurry to give instructions before students settle down or before they finish their task at hand. The fifth principle is advance organizer, which means that we should pay attention to the link between new and old knowledge when giving instructions. The sixth is that instructions should be complete, which means that we should tell the students the purpose, procedure, time and arrangement of the activity. The last principle is that we should tell our students the time for the start and the end of the activity so that they may plan their time accordingly.

3.Activity Selection Strategies

The strategies for selecting types of activities in class include participation-oriented, activity-oriented and goal-oriented strategies.

A participation-oriented strategy involves different participation models, including whole-class activity, group work, pair work and individual activity. Our monitoring and participation are different depending on the participation model we use.

An activity-oriented strategy means different activities may require different participation models. For example, a whole-class model is often used for presentations, and pair work is often employed for role-plays.

A goal-oriented strategy means that activities are chosen with the different goals of the activities in mind. These activities are classified according to various criteria. One classification is based on how we deal with language materials: we may classify activities as presentation, comprehension, application, or consolidation activities. A further classification is according to the role our students play in the activity: we may divide activities into communication of information, role-plays and tasks. The final classification is according to the role of the activity in classroom management: we may categorize the activity into “motivating type” and “stabilizing type” (ibid. 157).

We may use the activities mentioned according to our own needs, but no matter what kind of activity we want to use, careful preparation is a must.

Presentation activities usually take the form of whole-class work (ibid.). After students' presentations, we must guide the whole class to engage in the material presented. We may lead a Q&A or discussion based on the presentation in order to enhance the students' learning. This kind of interaction can offer the students who did the presentation a sense of achievement.

Reproduction exercises and dialogues may take the form of pair work, which can optimize the use of class time, giving every student opportunities to practice. In this kind of activity, what our students are most worried about is that they cannot identify each other's mistakes. To address this concern we may walk around and listen in order to note the common problems. Then, we may summarize what has been done at the end of the activity. In this way, our students can express their ideas (meaning), notice the forms, and become aware of their own problems through language use.

Word games, plays, projects and interviews may take the form of group work. If we choose to use group work, preparation is of primary importance. We must also give clear instructions, making our students aware of the aim, specific procedures, what they should do, the final outcome and how the final presentation should be conducted. Only when they are totally clear about the activity should we start. At the end of the activity, we should summarize what has been achieved and what can be improved.

III.Problems and Suggestions in Classroom Management

There are some problems we are sure to encounter in teaching.

●The class may be too large.

●The group work does not go smoothly.

●There are some discipline problems.

●We are forced to deviate from our lesson plans.

In anticipation of these, we should come up with potential solutions.

1.Discipline

The four strategies for maintaining discipline in the classroom are based on our students, the whole class, the tasks we design and who we are in class. Firstly, we should try to use different techniques to manage behavior; for example, we may name students when asking questions. Secondly, we may involve the class in maintaining discipline by, for example, asking students in a group to monitor each other. Thirdly, our students should be encouraged to have self-control and manage themselves. We may ask them to take charge of class assessment. Lastly, we may use tasks like games to maintain discipline (ibid.) .

When there are discipline problems, we should analyse what the causes may be, and then try to resolve the issues. Brown (2001: 417) offered some pointers for keeping classroom discipline:

●Gain the respect of your students by treating them all fairly.

●State clearly and explicitly to your students what your expectations are regarding their behavior in class (such as speaking up in class, taking turns, respect for others, group work, attendance, and homework) .

●Be firm, but warm, when dealing with students who do not live up to these expectations.

●If a reminder or reprimand is warranted, do your best to preserve the dignity of the student.

●Try, initially, to resolve disciplinary matters outside class so that valuable class time is not spent focusing on one student.

2.Midstream Lesson Changes

We are often called upon to deal with the unexpected in the classroom. Sometimes, we may deviate from our original plans. For example, we ask our students to discuss an issue we assigned to them, and find, after a while, that they have changed the topic and are having a heated discussion about other issues. We are caught in a dilemma. Should we stop them and stick to our lesson plan or should we let them go on with their authentic communication in English? Brown (ibid., 414) offered this principle, “The key is poise. We should stay calm, assess the situation quickly, make a midstream change in our plan, and allow the lesson to move on.” Harmer reinforces this in saying “Good teachers are flexible enough to cope with these situations; they are able to react quickly to the unplanned event” (Harmer, 2000: 6).

3.Large Class

If we are teaching a large class with students of different proficiency levels, we can use selected techniques to achieve the best teaching outcome. Usually we may employ pair and group work to offer opportunities for more students to practice their English, giving them a sense of belonging in the class. When our students are at different levels, we can use different materials, do different tasks with the same material, or adopt a strategy of peer help and teaching (ibid., 127) . We can also design open-ended tasks for our students. For example, when we are teaching how to ask for permission or how to make a request, we may offer five to six different scenarios, give our students a time limit and ask them to practice in groups. They may finish one, or finish all of the assigned tasks according to their own levels (Parrish, 2006), which will offer them all a sense of achievement.

In our teaching, designing different tasks with the same material is more practical than using different materials. We can take listening skills development as an example. We can use the same listening material to design different tasks for our students (e.g. reproduction exercises for students at higher levels, simple questions for those at lower levels). If we have to listen to the same material several times, we may design additional tasks of different difficulties for higher competence students (e.g. dictation of sentences in the audio), while for those students with lower competence, they may only need to find the answers to the questions. Both groups can have a rewarding experience in class.

Next, let’s do some other exercises.